I only "understand" it in terms of an old StarTrek story, where they stated it was "impossible" to reach Warp10.

Why? Because at Warp10, you would travel half the remaining distance to your destination each unit of measure - but never get there.

EG: The first second, if your destination was 1 foot away ... you would travel 6 inches.

The second second, you would travel 3 inches (half the remaining distance of 6 inches).

The third second, you would travel 1.5 inches (half the remaining distance of 3 inches).

And so on, and on, and on.

Essentially, you would NEVER reach your destination. Because the distance you traveled kept getting smaller and smaller.

Anyway ... It's a logarithmic decrease, rather than a straight decrease.

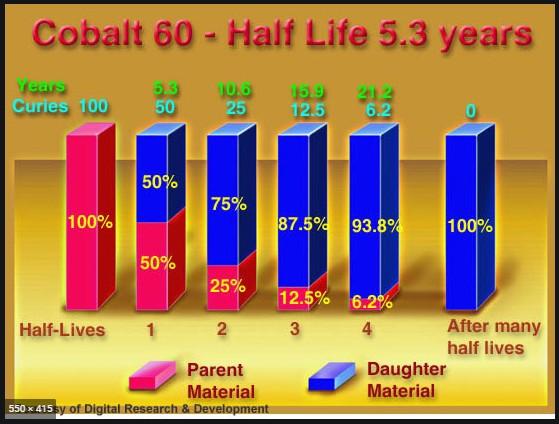

Here's a chart, for the half-life of Cobalt 60:

But with increasing frequency, the safety problems that surround any massive piece of industrial equipment have prompted public questions about whether nuclear power is worth even the remote risk of a accident. Most experts agree that the American nuclear industry is in serious trouble. In the past few years, utilities have been canceling orders for reactors. This is in part because the recent growth in the demand for electricity has been less than predicted, in part because the cost of reactors has increased faster than expected (to about $1 billion each), and in part because of the growing political opposition to nuclear power.

After previewing “The China Syndrome” in different cities, the nuclear power experts were each asked four questions and invited to make any additional comments they wished.

The questions:

• Is there a danger that a “meltdown” — the most serious kind of possible reactor accident — could be initiated, as the film depicts, by a minor problem in the plant?

If impossible or highly unlikely, is there another equally simple way meltdown might be triggered?

• Is it credible or possible, as the film has it, that a utility would manipulate information to hide the fact that a contractor falsified vital safety records?

• Does the film make a worthwhile contribution to the present debate over nuclear energy — or will its influence be harmful?

Most of the experts agreed that minor mishap at a nuclear power plant could trigger a serious accident, but strongly disagreed with each other on the probability of this occurring.

Dr. Norman Rasmussen, a professor of nuclear engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who has long championed atomic energy, directed a massive study on the safety of reactors for the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. The final report, issued in 1976, concluded that the possibility of the most serious kind of reactor accident occurring was as remote as a huge meteor slamming into a major city; statistically, it said, a meltdown might occur once in one million years. The N.R.C., while praising the methods of the Rasmussen study, recently concluded there was not enough information to judge the possibility of an accident in a precise way.

https://www.nytimes.com/1979/03/18/archives/nuclear-experts-debate-the-china-syndrome-but-does-it-satisfy-the.html

Following the lift the alcohol tax in 1906, there was much promotion, both by the federal government and the national media, of ethyl alcohol fuels as a promising and cheap alternative to petroleum-based fuel (at the time ethanol from corn was quoted by the New York Times as up to 60 percent cheaper than gasoline). According to Senator Champ Clark, who served in the early 1900's, oil producers such as Standard Oil were publicly against the "free alcohol" bill and supported retaining the alcohol tax. Interestingly, automobile manufacturers supported ethyl alcohol as an alternative to gasoline, as most manufacturers designed their engines to run on pure alcohol fuel, in addition to gasoline and any composite blends. Ethyl alcohol was widely considered as preferable to gasoline because it was relatively clean burning and because alcohol markets would be far less volatile than those of gasoline as a result of the the renewable nature of its source. Despite the original praise of ethyl alcohol and its promise as a gasoline alternative, it largely failed in the early 1900's. Fewer alcohol distilleries than expected were built, and as a result of low supply, prices became non-competitive. The discovery of plentiful oil reserves in Texas in the early 1900's re-established gasoline as the fuel of choice in the United States.

Much research was conducted in the United States and internationally on ethyl alcohol, aimed at characterizing its performance relative to gasoline. Many of the technical benefits of alcohol resulted from it high octane rating, which prevented engine knocking (a common problem in automobile engines running on pure gasoline) and also increased the the the maximum operational engine pressure ratio, thus increasing maximum horsepower generation. Some problems that were noted were trouble starting, low volatility, and sensitivity to moisture, though these were generally considered minor drawbacks in comparison to the benefits of a higher octane rating. Despite the significant scientific support generated, forces in favor of petroleum such as the American Petroleum Industries Committee were able to paint ethanol as an entirely inferior fuel in front of Congress on multiple occasions. The result was that the oil industry was able to block up to 40 state and federal bills supporting alcohol-gasoline tax incentives and blending programs during the 1930's. The alcohol-blending support revived in the 1930's following the promising results of ethyl alcohol research (dubbed farm chemurgy)was stamped out not by free-market competition, or by lack of supply as in past instances, but by political and questionable business practices carried out by the industries it threatened. Besides the political lobbying against alcohol fuel incentives and blending programs, some companies, such as Ethyl Corp., went as far as denying contracts to petroleum refineries and wholesalers who produced blended varieties of gasoline.

So it wasn't as much the petroleum industry, as much as the lack of alcohol distillers, that "killed" the alternative fuel.